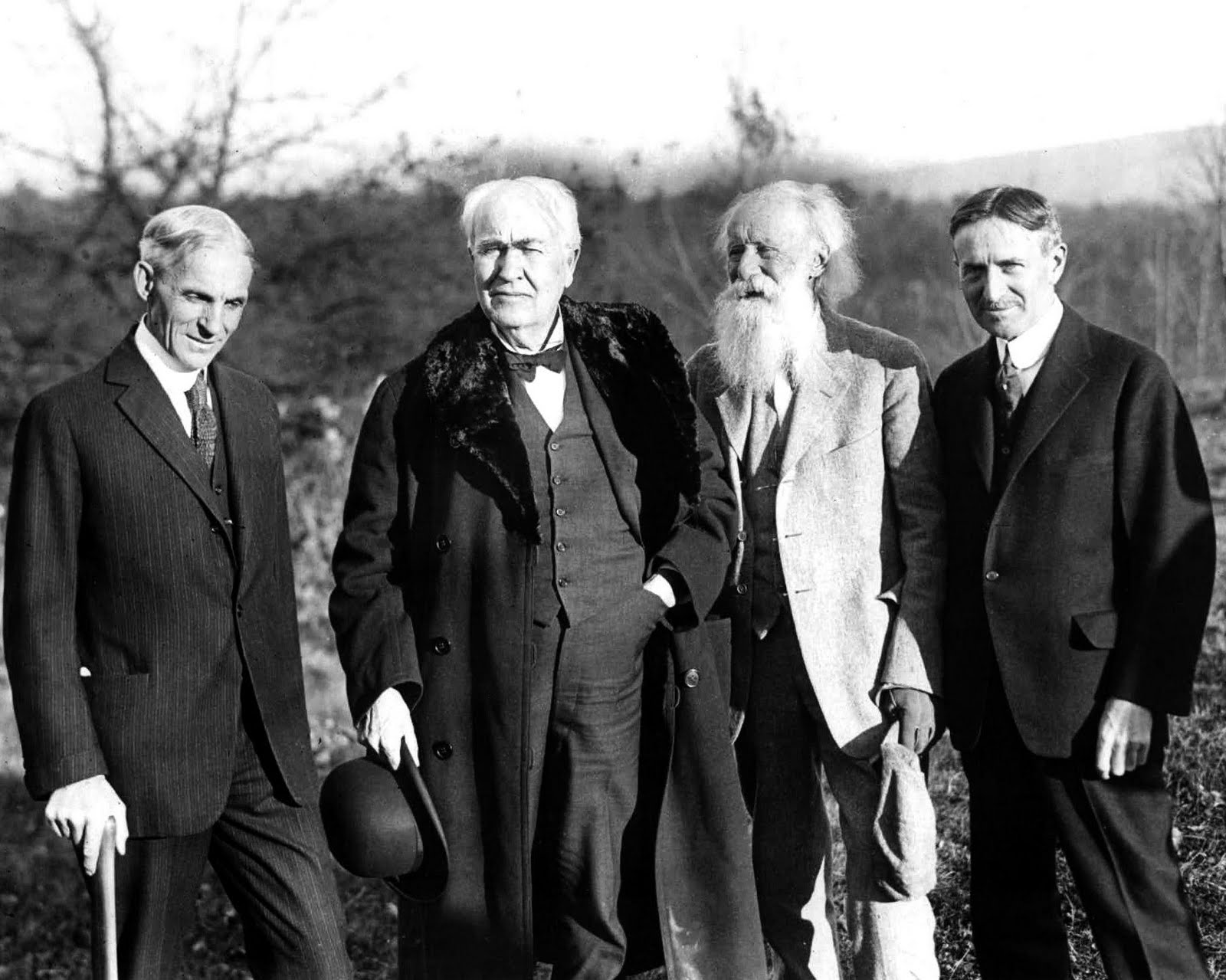

Burroughs was a critic of the era of mass production, of which Ford’s cars and Edison’s light bulbs were potent symbols, but he had been courted by Ford, and his presence on the trips was a symbol of two American centuries meeting around the campfire.

Henry Ford was a farm boy who couldn’t read a blueprint. He was nervous and energetic, emotionally immature, and puritan in matters of intoxication. A genius with his hands rather than his head, he did not read many books, but he did read the works of John Burroughs, due to his interest in birdspotting. In December 1912, Ford wrote to Burroughs telling him that few persons in the world had given him as much pleasure as he had. In return, he wanted to do something for Burroughs. He wanted to give him a car. He assured Burroughs that it was not a publicity stunt, and the car could be there by January.

Burroughs had misgivings. He was seventy-five years old, an advanced aged for a learner driver. Friends persuaded him to accept the gift and the old man spent the winter attempting to master it, with comically haphazard results. Behind the wheel, he was easily distracted by rare birds or plants, and would take his eyes off the road to follow its flight, his white bushy head rattling as the car bumped over the farm track. Driving scared him. He was not the master of the car. This technology was an unbroken horse with a will of its own.

The gift achieved Ford’s intended aim, which was to meet his hero. In June, Burroughs travelled to Detroit to visit Henry Ford. The two men got on. After a tour of the Ford factory, Burroughs described the manufacturing process with the eyes of a nature writer; it was a “wilderness of men and machinery covering over forty acres. The Ford cars grow before your eyes, and every day a thousand of them issue from the rear.” After returning home to Roxbury, Burroughs went to park his car in the barn but “it run wild”, bursting through the side of the building and rattling on to a drop of fifteen feet. The forward axle went out over the edge but the wheels caught enough purchase to prevent the car landing at the foot of the steep hill. He regarded the accident with shame. The old fool should not have dabbled with technology.

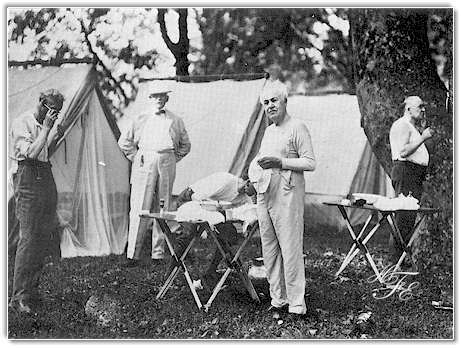

Ford and Burroughs’ visited Thomas Edison’s home in Fort Meyer in Florida. Edison was a decade younger than Burroughs, and sixteen years older than Ford, or as Burroughs put it, “Mr Edison and Mr Ford are as young as I am, but no younger.” The public images of all three men relied upon their physical vigour. Burroughs was uncommonly fit for a man in his seventies. When dallying at a cliff edge, it was suggested to him that he show caution and step back. In defiance, the old man sprang onto this hands, his feet in the air, to prove there was no danger. In his early fifties, Henry Ford could run like a deer, and prided himself upon his high kicks and leaps. Edison had many famous pronouncements concerning diet and sleep, claiming that he subsisted on four or five hours rest a night and ate a sparing diet of toast and hot milk. Their camping trips saw the suspension of Edison’s frugal regime; as Burroughs’ diary of his first visit to Florida relates, “We begin the day so late here… Edison sleeps ten to twelve hours in the twenty-four; says he can store up enough sleep to last him two years.”

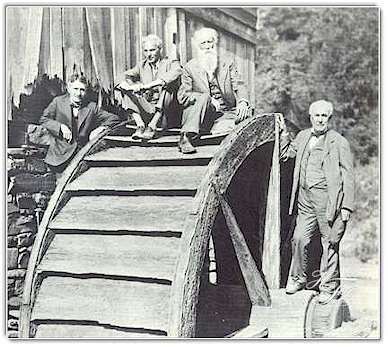

Edison suggested that the men and their wives should take a break from Fort Meyer and go down to the Everglades and revert back to nature. “We will get away from fictitious civilisation,” said Edison to a reporter, “and we expect to be happy and learn much.” In early March, the party slipped away for two days camping, with two guides and a cook. The trip was a success. More ambitious camping trips were to follow, billed by The Washington Times as “Edison and Ford to go back to nature”.

Taken from The Art of Camping: The History and Practice of Sleeping Under the Stars by Matthew De Abaitua and published by Penguin