I was lying in my tent in the middle of a cold night when I received an urgent call from nature. I often camp in remote spots, seeking a connection with the land and respite from creditors. The call was urgent, and so I clambered over my sleeping wife, out of the inner tent and into the cold chamber under the flysheet.

I was wearing a thermal vest, long johns and thick hiking socks. To go outside, I would need footwear. In the corner of the tent, my boots – which require some lacing – and next to them, a pair of sandals. I gazed down at my stockinged feet, back at the sandals, and then at my sleeping wife:

Could I do it? Could I wear sandals and socks?

Sandals and socks are reviled because they are a philosophical cop-out. The sock we associate with the shoe, with keeping one foot in the compromises and confinements of city life. The sandal yearns for the simple life, the toes wriggling free and tickled by spears of dewy meadow grass. To put a sock between the foot and the sandal is an ugly compromise.

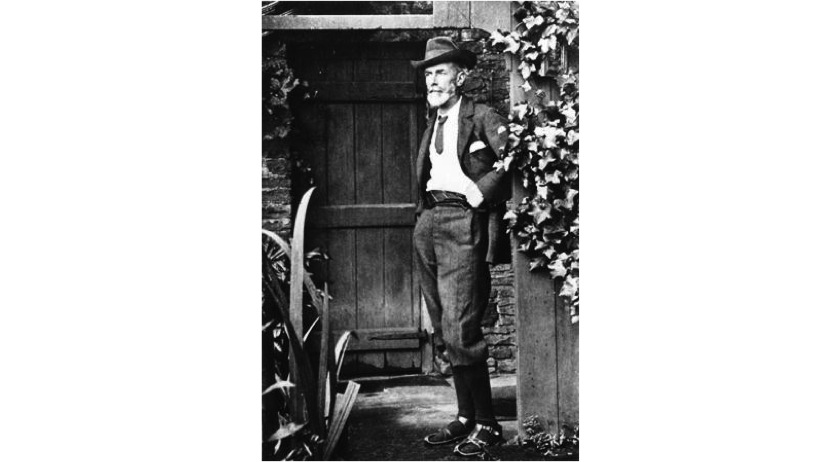

Although Edward Carpenter could cast off the repressive expectations of Victorian society, he could never quite take off his socks

The shoe is a “leather prison” for the toes. So declared Edward Carpenter, a free-thinking socialist of the late Victorian period who was responsible for introducing the sandal into bohemian culture. A friend sent Carpenter two pairs of Kashmiri sandals from India, and he set about copying the design and distributing them to contemporary free-thinkers, in partnership with George Adams who he set up as sandal maker-in-chief.

Carpenter was gay, overtly so. His discretely circulated pamphlets did much to prepare the ground for what a same sex comradeship might be in the modern world. Born in Hove and educated at Cambridge, he set up home in Millthorpe in the countryside beyond industrial Sheffield, attracted both by the radical potential of the labour movement and by the sexual potential of the labourers. He met one such labourer, George Merrill, on a train. The two men enjoyed an open relationship, and Millthorpe became a site of pilgrimage for seekers of the simple life.

How would the spectacle of me in socks and sandals affect my wife? The marriage would survive, but it is likely that her libido would not

Although Edward Carpenter could cast off the repressive expectations of Victorian society, he could never quite take off his socks. Photographs of the lean bearded “Saint in Sandals” show him wearing them with socks pulled up to the knee. Freedom was more important that the restrictions of style: he dispensed with waistcoats, underlinen and ties and wore instead a minimal outfit of woolly shirt, coat and pants. His sandals cost 10s 6d, less for children, and were a symbol of belonging to the progressive cause.

All these thoughts assailed me on that cold night in my tent. How would the spectacle of me in socks and sandals affect my wife? I wasn’t worried about the damage that it might do to our marriage. Our marriage has solid economic underpinnings, and there are children involved. The marriage would survive, but it is likely that her libido would not. I checked that she was soundly asleep, and then carefully slipped on the sandal.

Archeological analysis of fibres found on Roman sandals suggest that when the soldiers were in colder climes, such as Britain, the sandal was worn with socks

The sensation was obscene. The thickness of the sock caused the strap of the sandal to tighten indecently around the foot. The sandal was a Birkenstock, a German family company who made contoured shoes contemporaneous with Edward Carpenter’s sandal business. The German people are associated with the sandal and the sock combination, a Teutonic assertion of pragmatism over aesthetics. One wonders if they even remove their white ankle socks during intercourse.Birkenstocks did not get into sandals until 1965 during the American revival of the simple life or hippy movement.

The sandal was mankind’s first article of footwear. In the age of Homer, both sexes wore a wooden sole fastened to the foot by thongs. The Mogollon Indian in Southwest America plaited their sandals from the leaves of the Yucca tree. In Roman times, the sandalium worn by women was a sole with a piece of leather covering the toes and was worn mainly indoors. The soldiers of the Emperor wore the caliga, a heavy and high-laced boot that was open at the toe. Archeological analysis of fibres found on Roman sandals suggest that when the soldiers were in colder climes, such as Britain, the sandal was worn with socks.

Today the British army issue sandals that are man-made with velcro fastenings. Far more appealing than these are the Northwest Frontier Chaplis worn by the Indian army during campaigns in the 1930s; with two thick leather straps crossing a tongue, only the merest peep of the toes is visible, thereby sparing passersby the sight of your ten blind blunt-headed worms.

In my sandals and socks, I went out into the night to heed the call of nature. It was the moment before the moment before dawn, and the land seethed with anticipation. Carpenter and his sandals stand for the lost mystical socialism of Albion; a place where the working man and the high-minded type could join together to exceed the bounds of the acceptable and push away the deadening influence of mindless consumerism. This mystical socialism did not survive the Second World War. Sandal-wearing cranks were seen as an impediment to the credibility of socialism. George Orwell famously railed against “every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac… in England.”

In his essay On Sandals and Simplicity, GK Chesterton also took the sandal-wearers to task. He complained that advocates of the simple life would make us simple in the things that do not matter – diet, costume, etiquette – and complex in the things that do – philosophy and spirituality. The mystical socialist believed in plain living and high thinking. Chesterton, the scruffiest man in England, corpulent and windblown, sought the opposite: high living and plain thinking.

In my socks and sandals, I walked across the meadow to the witchy silhouettes of the copse, where I satisfied the masculine urge to urinate against the vertical. The black tops of the trees thrashed around in a bohemian dance. Grainy bands of indigo lay over the land. I felt the spirit of vitality move within me, the urge to cast off all clothing and to run amok as a natural animal. The wind goaded the tree tops into complete self abandonment. Would I join them?

No. Donning the sock and sandal was a transgression that threatened my very being! What next: speedos in the office? Trainers? The age of mysticism is past. I tromped back across the meadow, removed my sandals and cast them into the undergrowth. Never again would I be tempted by the comfortable compromise of the sock and sandal. From that night onward, my toes would serve out a life sentence in brogue and Brasher boot.

shoes